How can Christians legitimize a God who orders the genocide of nations?

Joshua 6. God tells Israel to take Jericho, and the text says the city was “devoted” to destruction: men, women, young and old, even animals.

1 Samuel 15. God tells Saul to strike the Amalekites and “not spare” them.

Numbers 31. Moses is told to take vengeance on Midian, and the instructions are brutal.

And critics like Richard Dawkins have pointed to these passages and basically said: “See? The Bible’s God is a moral monster.” (Dawkins, 2006).

So today we’re doing something most people avoid. We’re not going to pretend these texts are easy. We’re going to walk straight into them and ask: What are we actually reading, what did it mean back then, and what does it say about God’s justice and mercy?

Welcome back to Word for Word, I’m Austin Duncan. Today might be the hardest episode we’ve done so far. And I mean that.

Because we’re talking about passages where God commands what looks, on the surface, like the destruction of whole people groups. If you’ve ever read Joshua, or parts of Samuel, or Numbers, and you felt your stomach turn, you’re not crazy. That reaction is human. Let me say this up front, and I want you to really hear me: If these passages don’t bother you at all, you might not be reading closely enough. These are not “cute Bible stories.” They’re heavy. They involve real death, real fear, real consequences. But here’s the other thing I need you to hear just as clearly: Being disturbed isn’t the same thing as disproving something. Sometimes the most important questions are the ones that make you uncomfortable.

So today we’re going to do three things:

We’re going to read these conquest texts like grown-ups, which means we’ll talk about ancient warfare language and context. This is where a lot of confusion starts. (Younger, 1990; Kitchen, 2003).

We’re going to talk about why judgment shows up at all, and why Scripture frames this as justice, not racism or random cruelty. (Copan, 2011; Copan and Flannagan, 2014).

We’re going to tackle the questions you’re already thinking, especially the big one: “What about the children?” (Craig, 2007; Copan and Flannagan, 2014; Aquinas, 1947/1265–1274).

I also want to say with all of this, I’m not trying to win a debate. I’m trying to help you build a framework that can actually hold the weight of these texts without collapsing. Also, quick note: if you’re new to this series, this episode connects directly to earlier questions we’ve covered, like God’s foreknowledge and why God allows evil. Those aren’t side topics. They’re part of the same puzzle.

Alright. Let’s name the problem clearly.

The texts everyone brings up

Here are the three “headline” passages.

Jericho

Joshua 6:21 describes Jericho being “devoted” to destruction, including animals.

Amalekites

1 Samuel 15:3 includes language about not sparing, including children and infants.

Midian

Numbers 31 includes commands that are difficult to even read out loud.

This is why Dawkins swings hard at the Old Testament, describing God with terms like “bloodthirsty” and as an “ethnic cleanser.” (Dawkins, 2006). And he’s not alone. Even Christians admit these are the passages that make people cringe, stall out, or walk away. (Copan, 2011). So the question is not, “Do these passages sound awful?” They do. The question is:

What exactly is happening here, and what does the Bible itself expect us to understand?

To answer that, we start with a piece most modern readers miss.

First lens: Ancient war writing is not modern reporting

Let me give you a modern example first.

If your team wins 52–10 and you say, “We destroyed them. We wiped them out,” nobody calls the police. Everyone understands you’re using standard victory language.

Now take that idea and multiply it by an ancient world where kings wrote battle accounts the way hype videos are made today: bold claims, sweeping statements, “total victory,” “they were erased,” even when that plainly wasn’t literally true.

That’s not me making excuses. That’s a major conclusion from serious scholarship comparing the Bible to other ancient Near Eastern conquest accounts.

“Utterly destroyed” language was often conventional rhetoric

K. Lawson Younger Jr. did foundational work here, showing that phrases like “all the land,” “left no survivors,” and “totally destroyed” function as a kind of hyperbolic conquest rhetoric shared across the ancient Near East, not as a strict headcount report. (Younger, 1990).

Kenneth Kitchen gives a classic example. Egyptian Pharaoh Thutmose III could claim an enemy was “annihilated totally” as if they no longer existed, even though they absolutely did exist and fought later. Kitchen also points to the Mesha Stele, where the Moabite king boasts that “Israel has utterly perished for always,” which history immediately proves false. (Kitchen, 2003). The point is not “they lied,” the point is: everybody understood the genre.

This matters because Joshua uses that same style of language.

The Bible itself signals this kind of rhetoric

Matthew Flannagan highlights the internal evidence. In Joshua 10:20, the text says Israel “finished destroying” their enemies, and then, almost in the same breath, it says survivors escaped into fortified cities. (Copan and Flannagan, 2014; Flannagan, 2010). And zoom out and you see what people often call the Joshua-Judges “tension”:

Joshua 11:23 says Joshua took “the entire land.”

Joshua 13:1 says there’s still “very much land” left.

Judges 1 repeatedly says groups of Canaanites “persisted” in the land.

If you read Joshua like a modern press release, you think, “Contradiction.” If you read Joshua like an ancient conquest account, you recognize a familiar pattern: victory-summary rhetoric, followed by the ongoing reality of incomplete occupation. (Younger, 1990; Kitchen, 2003; Copan and Flannagan, 2014). So when people say, “The Bible claims total extermination,” the more careful answer is: the Bible uses total-victory language, the same way surrounding cultures did, and then the Bible itself shows ongoing survival and presence. That doesn’t solve everything, but it’s a big step, because it shifts what we picture.

Second lens: What were these “cities,” really?

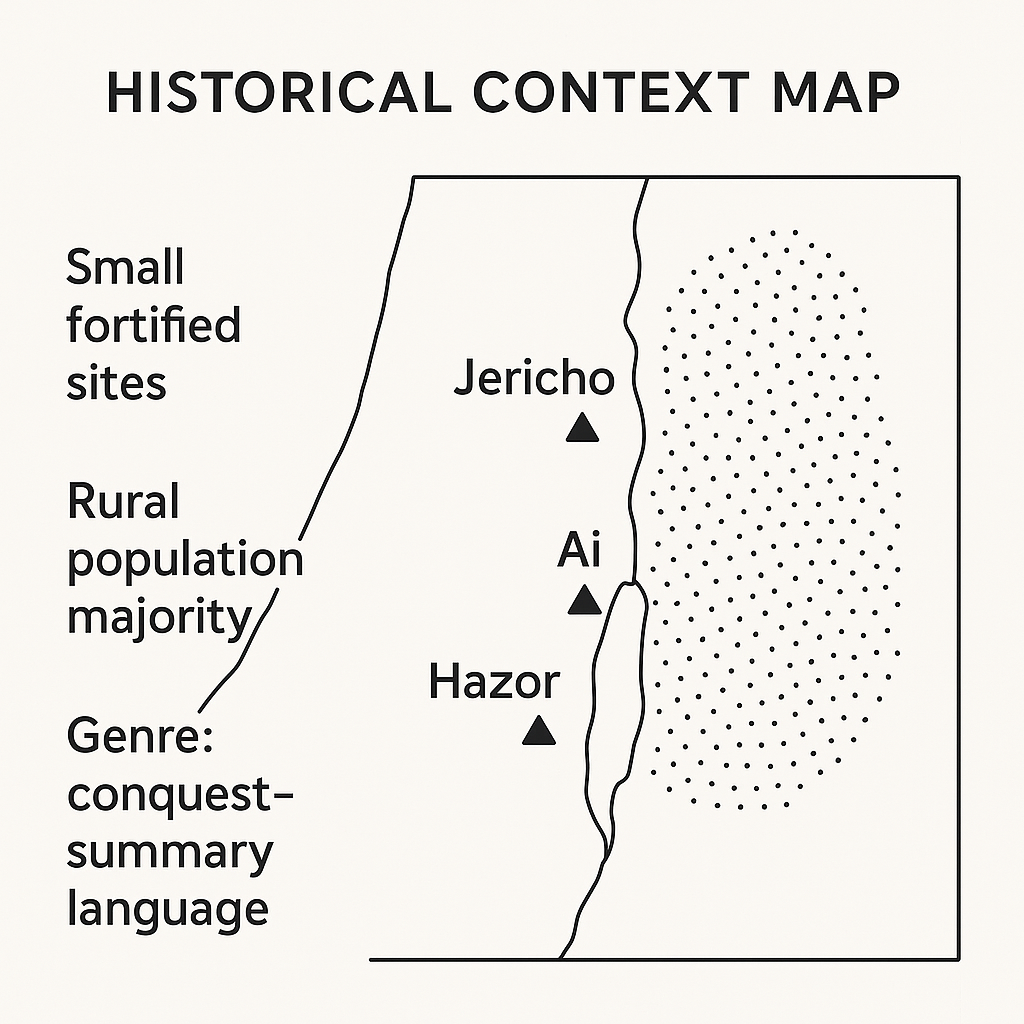

Most of us imagine ancient “cities” like modern cities. But archaeology and demographic studies paint a different picture.

Jericho was small

Jericho (Tell es-Sultan) was only a few acres inside the walls, with the broader area still modest by modern standards. (Garstang, 1931; Kenyon, 1957–1958; Mazar, 1990). Whatever Jericho was, it wasn’t New York.

Hazor was big for the region, but still limited

Hazor is described as a leading city in Joshua 11, and it’s one of the largest tells in the region, with estimates sometimes placed in the tens of thousands at peak, not hundreds of thousands. (Ben-Tor, 2016).

Most people did not live inside the fortress cities

Population studies suggest that in many ancient settings, only a minority lived in the walled urban centers, while most people lived in villages and worked agriculture. (Broshi and Gophna, 1984; Kennedy, 2013). This connects with Paul Copan’s point: some sites described as “cities” functioned largely as administrative and military centers: king, officials, soldiers, and the religious infrastructure tied to the ruling class. (Copan, 2011). Now, does that mean “no civilians ever died”? No. Ancient war was brutal and messy. But it does correct the cartoon version where Israel is pictured doing a door-to-door sweep through peaceful suburbs.

Archaeology also reminds us: these locations are debated

Serious scholars acknowledge tensions between some archaeological timelines and traditional conquest dating, especially with Jericho and Ai. Jericho’s destruction layers have been debated, with Kenyon’s work and later radiocarbon discussions often coming up; Ai (Et-Tell) has its own complexities, and alternative identifications have been proposed. (Kenyon, 1957–1958; Wood, 1990; Wood, 2000).

You don’t need archaeology to “save” the Bible, but archaeology can correct our assumptions about what kind of places we’re talking about.

Third lens: The Bible frames this as judgment, not ethnic hatred

This is where Genesis 15:16 becomes a key text. God tells Abraham that Israel will not take the land yet because “the sin of the Amorites has not yet reached its full measure.” That line matters because it says the timing is moral, not racial, not random, not greedy land-grab. Commentaries underline this: God is described as delaying judgment until guilt reaches a point where justice is due, which also implies long patience. (Ellicott, n.d.; Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges, n.d.). Clay Jones makes the obvious observation: if this were ethnic extermination, God could have told Abraham to begin killing Canaanites immediately. Instead, there’s a long delay, which is the opposite of a race-based purge. (Jones, 2009).

And Deuteronomy is explicit: Israel is not to think they’re morally superior. They’re told: it’s not your righteousness, it’s the wickedness of these nations, and Israel will face the same judgment if they become the same. (Copan, 2011; Copan and Flannagan, 2014). This is one of the strongest arguments against the “racist genocide” label: God judges Israel too, using Assyria and Babylon later, when Israel copies the same sins. (Copan, 2011; Wright, 2008).

So biblically, the logic is consistent:

God judges extreme corruption.

He does it with long warning and delay.

He does it without favoritism.

That is not how ethnic cleansing works.

The moral context: What was happening in Canaanite religion?

This is where people either lean in or check out. But we can’t skip it, because Scripture itself gives reasons, and archaeology and ancient texts give added context.

The Bible’s description is graphic

Leviticus 18 and Deuteronomy 18 describe practices God calls detestable: sexual exploitation, ritual practices, and child sacrifice. (Day, 2000; Zevit, 2001).

Outside evidence for child sacrifice is debated, but substantial

The Carthage Tophet is often discussed because Carthage was Phoenician, culturally connected to the broader Canaanite world. The site contains a massive number of urn burials over centuries. (Stager and Wolff, 1984). A major study in Antiquity argued the age distribution and context fits sacrifice rather than normal infant cemetery patterns. (Smith et al., 2013). There is scholarly pushback too. Schwartz and colleagues argued some remains could align with perinatal mortality patterns. (Schwartz et al., 2010). That debate should be acknowledged. But John Day summarizes the broader case: there are classical sources, inscriptions, and archaeology supporting the reality of child sacrifice in the Phoenician and Canaanite world, and therefore he argues there is no good reason to dismiss the biblical claims outright. (Day, 2000; Day, 1989). Shelby Brown also notes the distinctive nature of these practices in the Carthaginian setting. (Brown, 1991).

Ugaritic texts also illuminate moral and religious imagination

Clay Jones points to Ugaritic literature, including the Baal Cycle, to show that the religious world of Canaan included themes modern people would consider deeply corrupt, including sexual violence and exploitative patterns. (Jones, 2009; Smith, 1997).

Now, I want to be careful here. The goal is not to say, “They were bad, so anything goes.” That’s not the Christian claim.

The goal is to say what the Bible says: God is not portrayed as judging a basically normal culture for being the wrong ethnicity. God is portrayed as judging entrenched, multi-generational brutality and corruption, and the text insists the judgment comes after long patience. (Younger, 1990; Copan, 2011; Jones, 2009). This is why many Christian philosophers and theologians frame the conquest as a form of capital judgment on a society, not a race war. (Copan and Flannagan, 2014).

Mercy inside the judgment stories

Let’s now talk about the mercy that is present throughout the judgment stories, because this is one of the most overlooked parts of Joshua. If someone tells you, “The Bible shows God wants to kill every Canaanite no matter what,” Joshua itself challenges that.

Rahab

Rahab is a Canaanite woman in Jericho. She hears what God has done, confesses that Israel’s God is God over all, and she asks for mercy. (Joshua 2). She and her family are spared. She becomes part of Israel and is later honored in the New Testament and placed in the genealogy of Jesus. (Copan and Flannagan, 2014; Wright, 2008). Whether you’re Christian or not, that story matters because it shows the target is not skin color or ethnicity. The target is allegiance, corruption, and refusal to turn.

The Gibeonites

Joshua 9 is also important. The Gibeonites seek peace and are spared. Their later story shows they are absorbed into Israel’s religious landscape in surprising ways. (Copan and Flannagan, 2014). Even a summary from Belfast Bible College notes that within Joshua’s narrative logic, Canaanites who come to Israel’s God are received rather than automatically slaughtered. (Belfast Bible College, n.d.). So you have judgment, yes, but not an indiscriminate bloodlust. You also have an open door for those who turn.

“Okay, but how can God command killing at all?”

Now we’re at the point where historical context isn’t enough, because even if the rhetoric is stylized and the targets are limited, people still died. So the real question becomes: Can God ever be just in commanding death?

This is where Christians go back to first principles.

Principle 1: God’s rights over life

Scripture consistently presents God as the giver of life and the one who has authority over life’s boundaries. That claim is not unique to conquest stories. It’s a basic biblical worldview. (Aquinas, 1947/1265–1274).

Aquinas argues that because life is God’s gift, God can command its end without injustice in a way that creatures cannot. (Aquinas, 1947/1265–1274).

This is also why some Christian thinkers distinguish between:

What God may do, as Creator and Judge

What humans may do, as limited moral agents

Principle 2: God-command ethics

William Lane Craig defends a form of God-command ethics: moral duties are grounded in the commands of a holy God, and God is not under duties the way creatures are. (Craig, 2007).

Now, that does not mean “might makes right.” It means: in this view, the moral order is rooted in God’s nature, and God’s commands express that nature.

Craig also makes several clarifications that matter for this specific topic:

The goal in many texts is framed as driving out rather than hunting every person down. (Craig, 2007; Copan and Flannagan, 2014).

This is portrayed as a unique moment in biblical history, not a standing rule. (Craig, 2007; Keller, 2013).

The modern charge often assumes a definition of objective moral wrong that is difficult to ground in strict naturalism, which creates a philosophical tension for some critics. (Craig, 2007).

You don’t have to accept all of Craig’s framing to learn from his clarifications, especially the “unique moment” piece.

Principle 3: “Intrusion ethic” and why this is not a template

Tim Keller, building on ideas often associated with Meredith Kline, calls this an “intrusion” moment, where final judgment themes break into history in a limited way. (Keller, 2013).

Keller lists several reasons this is not a model for today:

Not race-based, proven by outsiders being received when they trust Israel’s God. (Keller, 2013).

Not imperialistic, with strict limits and prohibitions on plunder in key cases. (Keller, 2013).

It required direct revelation to Israel in that unique covenant setting. (Keller, 2013).

It functions as a limited preview of judgment themes. (Keller, 2013).

With a completed canon, Christians have no warrant to claim new conquest commands. (Keller, 2013).

Paul Copan also emphasizes this is not a justification for “holy war” today, and any modern application has to go through the New Testament’s framing of the people of God and the nature of the kingdom. (Copan, 2011; Copan, 2013).

The hardest question: “What about the children?”

Alright. Deep breath.

This is the question that makes people go quiet. It’s the question that can feel like the whole topic collapses into one brutal image. I’m not going to give you a glib answer. I don’t think Scripture invites glibness here. But I will give you four main pathways thoughtful Christians have taken, and I’ll be honest about what each one does and does not solve.

“Innocent” needs defining

From the Bible’s standpoint, adults are morally accountable, and these texts frame the adult society as deeply corrupt. (Copan, 2011; Jones, 2009). That still leaves children, who are not moral equals to adults in terms of culpability.

The “hope for those who die young” view

Craig argues that if God extends grace to those who die in infancy or early childhood, then their death is not their final harm, and it may even be their rescue from a future of corruption and judgment. (Craig, 2007). This view is not meant to make death “no big deal.” It’s meant to say: Christians see reality as larger than this life, so the ultimate moral calculus includes eternity. People often connect this with:

David’s words after his infant dies, expressing confidence of reunion. (2 Samuel 12:23).

Jesus’ posture toward children. (Matthew 19:14).

This doesn’t answer every question, but it directly addresses the charge, “God damns innocent kids.” That is not a Christian conclusion. (Craig, 2007).

Corporate judgment and future harm

Copan and Flannagan discuss moral reasoning in terms of a “crucial moral principle” about slaughtering innocents, and then argue that the conquest narratives are not straightforward cases of deliberately targeting innocents as innocents, especially once genre and the nature of the targets are considered. (Copan and Flannagan, 2014). They also argue the biblical rationale includes preventing the spread of practices that destroy the vulnerable, which makes the moral background part of the story, not a footnote. (Copan and Flannagan, 2014; Jones, 2009).

Honesty about moral tension

I want to say this carefully: even if you accept the theological arguments, you may still feel grief and revulsion. That is not spiritual immaturity. That is a normal human response to death. What Christians ultimately hold onto is Abraham’s question: “Will not the Judge of all the earth do what is right?” (Genesis 18:25). And the claim is: yes, God will. John Piper states God’s sovereignty over death in very blunt terms, and many people find his tone difficult, but his core claim reflects a common theological conviction about God’s rule over life and death. (Piper, n.d.). Even if you don’t share Piper’s delivery, the discussion forces you to decide whether you believe God is the kind of being who can be trusted with moral authority, or not. I can’t make that choice for you. But Christianity insists that the clearest window into God’s character is not Joshua 6 in isolation. It is Jesus.

And that leads to the next big misconception.

“Old Testament God vs New Testament Jesus”

People say: “The Old Testament God is harsh, but Jesus is loving.” But that separation doesn’t work if you take the Bible seriously. Paul Copan notes that this split resembles Marcion’s old move, which the early church rejected, because Christianity teaches the unity of God across both testaments. (Copan, 2011).

Tim Keller points out something that’s almost funny once you see it: many people object to conquest because it violates “You shall not murder,” but the Ten Commandments are in the Old Testament. So you can’t use an Old Testament moral standard to condemn the Old Testament God while discarding the Old Testament as unreliable. (Keller, 2013). And the New Testament is not silent about judgment. Jesus speaks of final judgment and hell more than most people realize, and Revelation uses intense war imagery to describe the final defeat of evil. (Keller, 2013; Wright, 2008). So the difference is not “Old Testament equals judgment, New Testament equals love.” The difference is where you are in the storyline:

In the Old Testament, God’s work is centered on a covenant nation in a land with a theocratic mission.

In the New Testament, God’s people are multi-ethnic, scattered among the nations, and the kingdom advances by witness, suffering, and love, not by conquest. (Walton and Walton, 2017; Keller, 2013).

Christians are not called to reenact Joshua. Christians are called to follow Jesus, who tells us to love enemies and refuse coercion. And that’s why the “modern application” question matters so much.

Modern application: What do we do with these texts today?

Let’s make this plain.

Christians do not have permission to do this today

The conquest was tied to a unique moment in salvation history. (Keller, 2013; Copan, 2011). Jesus says his kingdom is not advanced by the sword. (John 18:36). So any attempt to justify coercion, forced conversion, terrorism, or “holy war” from these passages is a misuse of the Bible and a rejection of the New Testament’s direction. (Keller, 2013; Copan, 2011).

So why are these texts still in the Bible?

A few reasons.

They confront our assumptions about evil. We often ask, “Why doesn’t God stop evil?” These texts are one answer: sometimes, God does, and it’s sobering. (Wright, 2008).

They warn us that corruption spreads. Judges is basically a case study in what happens when Israel fails to remove the practices God condemned. (Keller, 2013; Goldingay, 2011).

They point forward to the gospel. Judgment is real, which is why mercy matters. The cross is not sentimental. It is God taking judgment seriously enough to absorb it himself. (Wright, 2008).

They train us to read Scripture in context. John Walton and J. Harvey Walton emphasize that conquest texts need to be read within ancient categories and the Bible’s larger storyline, not with modern assumptions imported on top. (Walton and Walton, 2017).

How to talk with skeptics without being weird or cruel

If someone throws Joshua at you as a “gotcha,” here’s a healthier approach.

Step 1: Validate the emotional weight

“Yes, those texts are disturbing.” That’s honest.

Step 2: Clarify what kind of writing it is

Explain hyperbolic conquest rhetoric and how ancient accounts worked. (Younger, 1990; Kitchen, 2003).

Step 3: Clarify scope and purpose

This was limited in time, place, and target. It is framed as judgment on entrenched corruption, not ethnic hatred. (Copan, 2011; Copan and Flannagan, 2014).

Step 4: Include mercy stories

Rahab matters. Gibeon matters. These are not side notes. (Copan and Flannagan, 2014).

Step 5: Bring it back to Jesus

The Christian claim is that God’s character is seen most clearly in Jesus: enemy-love, self-sacrifice, refusal to coerce, and a call to repentance because judgment is real. (Wright, 2008; Keller, 2013). Also, it’s fair to point out that Dawkins’ way of presenting the Old Testament often ignores genre and historical context, and Christian scholars have noted that his engagement is thin compared to serious historical study. (Copan, 2011; Ruse in Copan, 2011).

You don’t have to be snarky. Just be steady.

So where does this leave us?

Let’s recap the framework.

Ancient war rhetoric used sweeping “total victory” language. That’s documented across the ancient Near East and within the Bible’s own narrative flow. (Younger, 1990; Kitchen, 2003).

The conquest targets and “cities” were not what modern people imagine. Many were small fortified centers, and most people lived rurally. (Broshi and Gophna, 1984; Kennedy, 2013; Copan, 2011).

Scripture frames this as moral judgment after long patience, not ethnic hatred. Genesis 15:16 is central here. (Ellicott, n.d.; Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges, n.d.; Copan and Flannagan, 2014).

Mercy is present inside the judgment stories. Rahab and the Gibeonites are proof the door was not slammed shut for outsiders. (Copan and Flannagan, 2014).

This is not a template for Christians today. The New Testament flips the posture: witness, suffering, love of enemies, no coercion. (Keller, 2013; Copan, 2011).

And here’s the heart-level conclusion. These texts are meant to sober us. Not to make us cruel. Not to make us smug. To sober us. If God is real, then evil is not just “unfortunate.” It’s accountable. And if you’ve ever been the victim of evil, that idea is not horrifying. It’s hope. At the same time, these texts should also make the gospel brighter. Because Christianity doesn’t say God stands far away from judgment and just throws lightning bolts. Christianity says God steps into the world, takes human flesh, and goes to a cross. So when I hold Joshua in one hand, I have to hold the cross in the other. If I ever start to think, “God must be cruel,” I look at Jesus suffering for enemies and I remember: whatever else I’m missing, I am not allowed to flatten God into a cartoon villain. God is just. God is patient. God offers mercy. And God will not let evil rule forever. (Wright, 2008).

How to read

- Genre

- Context

- Whole-story reading

- Jesus as the clearest window

How to respond

- Empathy

- Clarity

- Evidence

- Focus on the gospel

Conclusion

I’ll end with saying this: If you’re still uneasy, that’s normal. These passages involve death. We should never become casual about death. But after walking through the context, the genre, the moral background, the patience of God, and the mercy embedded in the story, I don’t think the best conclusion is “God is a monster.” I think the best conclusion is: God is serious about evil in a way we usually aren’t. (Jones, 2009). And the fact that God is serious about evil is exactly why mercy is not cheap and the cross is not a slogan. So I want to invite you to wrestle honestly and still hold onto hope. Because the story doesn’t end at Jericho.

The story ends at an empty tomb.

Sources used in writing this article:

Books and monographs

- Ben-Tor, Amnon. Hazor: Canaanite Metropolis, Israelite City. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 2016.

- Brown, Shelby. Late Carthaginian Child Sacrifice and Sacrificial Monuments in Their Mediterranean Context. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1991.

- Copan, Paul. Is God a Moral Monster?: Making Sense of the Old Testament God. Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2011.

- Copan, Paul. Is God a Vindictive Bully?: Reconciling Portrayals of God in the Old and New Testaments. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2022.

- Copan, Paul, and Matthew Flannagan. Did God Really Command Genocide?: Coming to Terms with the Justice of God. Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2014.

- Dawkins, Richard. The God Delusion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006.

- Day, John. Molech: A God of Human Sacrifice in the Old Testament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Day, John. Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000.

- Goldingay, John. Old Testament Theology, Volume 3: Israel's Life. Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2009.

- Goldingay, John. Joshua, Judges & Ruth for Everyone. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2011.

- Jones, Clay. Why Does God Allow Evil?: Compelling Answers for Life's Toughest Questions. Eugene: Harvest House, 2017.

- Keller, Timothy. Judges for You. Epsom: The Good Book Company, 2013.

- Kitchen, Kenneth A. On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003.

- Longman, Tremper III, et al. Show Them No Mercy: 4 Views on God and Canaanite Genocide. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2003.

- Mazar, Amihai. Archaeology of the Land of the Bible: 10,000-586 B.C.E.. New York: Doubleday, 1990.

- Smith, Mark S., ed. Ugaritic Narrative Poetry. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 1997.

- Trimm, Charlie. The Destruction of the Canaanites: God, Genocide, and Biblical Interpretation. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2022.

- Walton, John H., and J. Harvey Walton. The Lost World of the Israelite Conquest. Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2017.

- Wright, Christopher J.H. The God I Don't Understand: Reflections on Tough Questions of Faith. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2008.

- Younger, K. Lawson, Jr. Ancient Conquest Accounts: A Study in Ancient Near Eastern and Biblical History Writing. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1990.

- Zevit, Ziony. The Religions of Ancient Israel: A Synthesis of Parallactic Approaches. London: Continuum, 2001.

Journal articles

- Broshi, Magen, and Ram Gophna. “Middle Bronze Age II Palestine: Its Settlements and Population.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 261 (1984): 73-90.

- Craig, William Lane. “Slaughter of the Canaanites.” Reasonable Faith Q&A #16, 2007.

- Flannagan, Matthew. “Did God Command the Genocide of the Canaanites?” Paper presented at the Evangelical Philosophical Society, 2010.

- Gonen, Rivka. “Urban Canaan in the Late Bronze Period.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 253 (1984): 61-73.

- Hess, Richard S. “War in the Hebrew Bible: An Overview.” Bulletin for Biblical Research 7 (1997): 61-78.

- Jones, Clay. “We Don't Hate Sin So We Don't Understand What Happened to the Canaanites: An Addendum to ‘Divine Genocide’ Arguments.” Philosophia Christi 11, no. 1 (2009): 53-72.

- Morriston, Wesley. “Did God Command Genocide? A Challenge to the Biblical Inerrantist.” Philosophia Christi 11, no. 1 (2009): 7-26.

- Rauser, Randal. “Let Nothing that Breathes Remain Alive: On the Problem of Divinely Commanded Genocide.” Philosophia Christi 11, no. 1 (2009): 27-41.

- Schwartz, Jeffrey H., Frank Houghton, Roberto Macchiarelli, and Luca Bondioli. “Skeletal Remains from Punic Carthage Do Not Support Systematic Sacrifice of Infants.” PLOS ONE 5, no. 2 (2010): e9177.

- Smith, Patricia, Lawrence E. Stager, Joseph A. Greene, and Gal Avishai. “Cemetery or Sacrifice? Infant Burials at the Carthage Tophet.” Antiquity 87, no. 338 (2013): 1191-1198.

- Stager, Lawrence E., and Samuel R. Wolff. “Child Sacrifice at Carthage: Religious Rite or Population Control?” Biblical Archaeology Review 10, no. 1 (1984): 31-51.

- Wood, Bryant G. “Did the Israelites Conquer Jericho? A New Look at the Archaeological Evidence.” Biblical Archaeology Review 16, no. 2 (1990): 44-58.

- Wood, Bryant G. “Khirbet el-Maqatir, 1995-1998.” Israel Exploration Journal 50 (2000): 123-130.

Archaeological reports and dissertations

- Kennedy, Titus Michael. “A Demographic Analysis of Late Bronze Age Canaan: Ancient Population Estimates and Insights through Archaeology.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of South Africa, 2013.

- Mosca, Paul G. “Child Sacrifice in Canaanite and Israelite Religion: A Study in Mulk and Molech.” Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, 1975.

Ancient primary sources

- Merneptah Stele (Victory Stele of Merneptah), c. 1208 BCE. Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

- Mesha Stele (Moabite Stone), c. 840 BCE. Louvre Museum, Paris.

- The Baal Cycle (Ugaritic texts from Ras Shamra), 13th-12th centuries BCE.

- Annals of Thutmose III (Karnak Temple), c. 1458-1438 BCE.